I believe that human ingenuity is only matched by the equally human capacity for cruelty. Think about what we have achieved over the millennia—the great works, the stunning, almost incomprehensible technological leaps. Then think about how they were achieved, and the terrible choices we made to enable that progress.

At Ironbridge in Shropshire, you feel the push/pull of human inventiveness very clearly indeed. At first sight it seems bucolic—a small town hugging the banks of the River Severn, tucked into the lush green of the Ironbridge Gorge. The differences become clear once you see the structure after which the town is named.

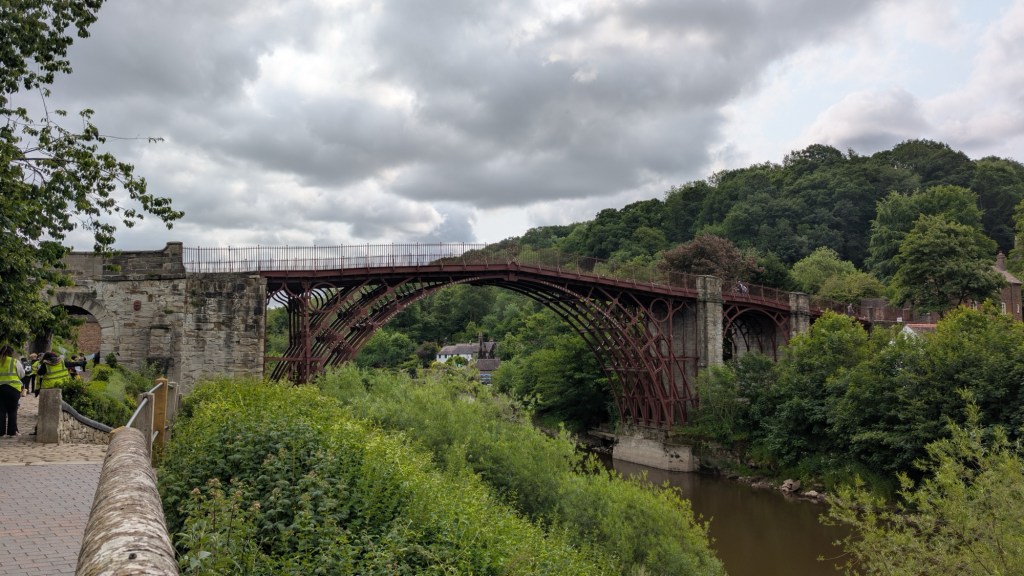

A great arch of red-painted iron connects the two banks of the river at the town square. It stands out against the quiet green like the wound left by a slashed sabre. From the 1780s it was a major ventricle through which trade and commerce could flow. The bridge is just a curiosity now, good for foot traffic only. But its importance can’t be understated.

It is the first span bridge built of iron, and the town it calls home is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. You see, Ironbridge is best known as the cradle, or more accurately the crucible, of the Industrial Revolution. If you want to understand how the modern world was built, this little Shropshire town is a good starting point.

The folk of Ironbridge take their role in history seriously. There are ten museums dotted around the site, some more walkable than others (to be frank, you really need a car to explore properly). There’s an award-winning living museum where you can awkwardly interact with costumed players in a reconstruction of Victorian times. The hard-core knowledge seekers, though, will follow their noses in a quest for fire.

The Old Furnace squats at the far end of a manicured courtyard like an abandoned temple to an ancient god. Its sides are stepped like a ziggurat, blackened and scarred through decades of flame. It was here, in the 1770s, that Abraham Darby perfected the art of smelting iron with roasted coke instead of coal, allowing for much cheaper production. His grandson would forge the iron which would span the Severn and give the nascent British Empire a symbol of the Englishman’s mastery over nature.

Wandering around the site or the many museums, you can feel the white heat of knowledge, experimentation and sheer will to create crackling in the air. The Old Furnace, long cold, reeks of carbon and iron, the bricks still strangely warm to the touch. That connection to the past is not sanitised or glossed over—Ironbridge may be proud of its history but it never turns from the suffering which went along with the Darby’s achievements. Every step of the process which led to the raising of The Iron Bridge was dirty and dangerous—from the mining to the transport to the smelting and pouring. Thousands died every year in the service of the Industrial Revolution.

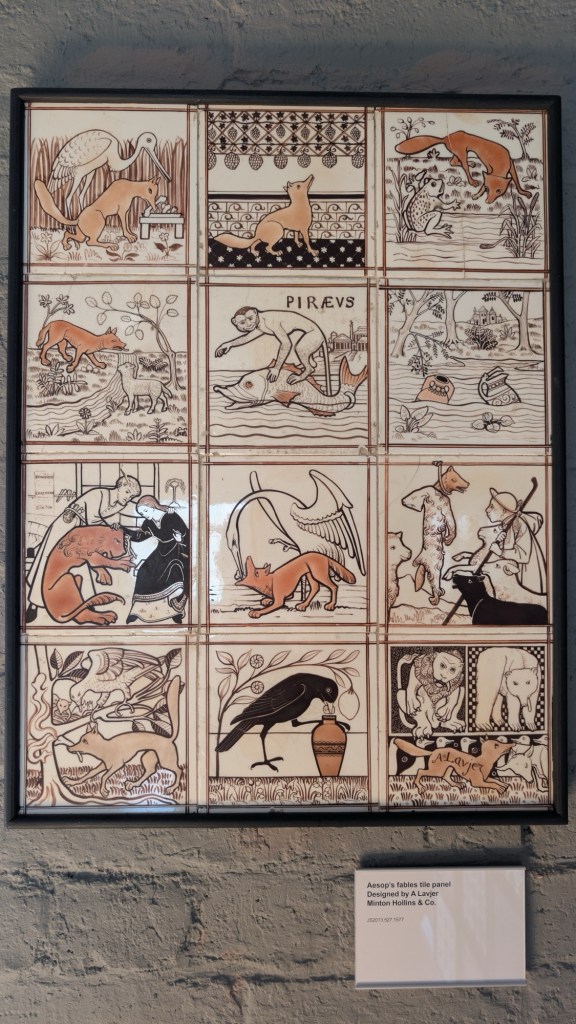

Over the river at Coalport and Jackfield, the fire burns differently but at similar cost. The area was a hub of pottery, particularly decorative tiles and fine china. The delicacy and artistry of the finished objects cannot be undersold. They were a key part of the British Empire’s export strategy. Coalport china graced the tables of the well-to-do from Birmingham to Bombay. The plates, bowls and vessels which came off the production line were status symbols, a perfect way to show off your wealth to your neighbours. Meanwhile the tiles rolling out of Craven Dunnill (which still produces on the original site) could be seen on pub walls, cladding butcher’s shops, even the tunnels of the new London Underground railway. The craftsmanship involved in pottery frequently boggles my mind—how on earth can these beautiful objects come unscathed from the fire?

The kilns at Coalport and Jackfield are less brutalist in form than The Old Furnace, taking the shape of high, wide-necked flasks. This shape allowed for even, steady distribution of heat—essential to ensure delicate porcelain and highly decorated tiles did not crack or shatter. But again, the folks who fed the kilns and dug out the clay led very different lives to those who would enjoy the products of their labour. The kilns would reach temperatures of 1000C, and the working conditions for a pottery worker gave little concessions to health and safety. Their time on earth had all three elements of a life you would not wish on anyone—nasty, brutish and short.

At Coalport we met a lovely woman on a pottery course. She was making saggers, the round clay trays which would cradle and protect delicate items as they were stacked in the kiln. She identified as a practicing witch, and her work was decorated with magical sigils and spell-signs. This warmed me somehow, and I wondered if women like her had carved protective wards into the kiln bricks and saggers in the past, as a way to guard the folk who risked their lives every day to feed the hunger for the trinkets they produced.

Heading east, Witley Court in Worcestershire offers a final vision of an England defined in flame. It was originally built as a humble red-brick house for the estate landowners in the 1630s. Successive families, connected to the iron trade, added onto the original structure until, by the 1870s, it had become one of the most palatial structures in the country. A status symbol like Coalport chinaware, but on a much larger scale. Think billionaire’s super-yacht and you’re in the ballpark.

Much of the reconstruction work was carried out under the direction of the Ward family, who owed significant iron-production facilities in the West Midlands. The scion of the clan became powerful enough to earn an Earldom—yet another example of the robber-baron formula which became the foundation of our current system of privilege and influence.

The Ward’s facilities at Round Oak Steelworks in Dudley were infamous for the callous indifference to the well-being of their workers. Health and safety was not a consideration. Round Oak was a death trap. An employee under the ‘care’ of the Earl of Dudley would only be expected to survive until the age of, on average, sixteen and a half.

If you made it to your twenties, you were considered lucky.

Visiting Witley Court today is a strikingly eerie experience. The frontage sparkles in the sunlight, the grounds are beautifully kept. On the hour every hour, a gigantic fountain depicting Perseus and Andromeda blasts gouts of water 120ft into the air. So far, so National Trust. It’s only missing the scones.

But once you step inside the building, things change.

The Wards left Witley in 1920, and its new owners didn’t have fortunes fed on the blood of their workers to keep it in prime condition. They lived in straitened circumstances in corners of the massive building, which gently mouldered and crumbled around them. In 1937, a fire swept through the Court, gutting it. There was no money available for restoration. The decision was made to simply let it rot.

Now managed by English Heritage, the shell of Witley Court is, on approach, a stunning riot of Palladian arches and columns, a bold clash of different architectural styles. Once inside, the bones of the place are open to the air. This is not a stately home. It’s Britain’s most opulent ruin. There are traces of the original red-brick building—an old archway, a mullion window. Scraps of wallpaper are visible, in the arsenic-green so beloved of Victorians. There are ghosts at Witley, for certain, and I was convinced I could smell smoke in the Great Hall. It’s all too easy to get turned around, unsure of your bearings, even though the outside is always clearly visible through the great, glassless windows.

The building is still used for film and photo shoots—an Indian couple, the bride in red, were directed by an eager director into moody poses between the pillars of the entrance hall during our visit. It would make a wonderful location for a post-apocalyptic movie or an experimental production of Shakespeare.

A fitting end to the tale would keep the Wards in residence when the flames tore through Witley Court—hubris punished in the manner by which their casual cruelty manifested. Sadly, that’s not the case. They drifted away years before, unaffected, uncaring, inviolable.

But I sense a karmic load at Witley, as if the phantoms of the Industrial Revolution set focus on this place as a lens magnifying the cruelty, until a spark was finally kindled and a debt repaid in flame. It makes for a more satisfying story, at least.

And in a larger sense, there’s a lesson we can take away from Ironbridge and Witney Court. The British Empire is gone but we as a nation carry on—showing our best face to the casual visitor, letting them wonder at the relics of our history, hoping they won’t notice the ugly hollowness beyond the shining facade we present so proudly.