Good science fiction is essentially a reflection of the times in which it was created.

Welcome to the world of tomorrow…

Welcome to the world of tomorrow…I couldn’t help but muse on that as I walked out into watery August sunlight, following a screening of Neill Blomkamp’s angry, political SF movie Elysium. It’s not a subtle piece, but then why should it be? It’s a parable with its roots in today’s societal structure. The super-rich have distanced themselves from the rest of us, and in Elysium they take the final logical step. They leave the planet altogether. They barely see anyone that’s not in their orbit as human.

The world they have left behind is not just in decay. It’s actively falling to pieces. Blomkamp, who shot to fame with the crumbling ghetto landscapes of District 9, ups the ante here, and turns Los Angeles, the city of angels, into a stinking slum. It’s the sort of place that people will risk anything to escape.

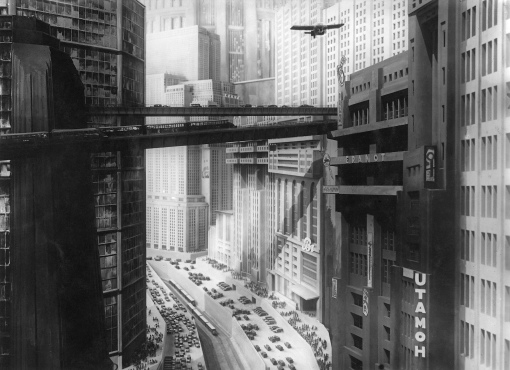

Dystopia in SF is hardly new or original. One of the key formative texts in filmed science fiction is Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, set in a concrete hell of skyscrapers and pounding heavy industry. This, along with Chaplin’s Modern Times, keys into the common fears of that early quarter of the last century: what happens if industrialisation and automation runs amuck? As Lang’s characters become mere components in a machine, and the villain is revealed to be a robot, his visuals underpin the narrative explicitly. The settings are as important to the plot as Freder and Maria.

Crumbling infrastructure is more prevalent than pristine surfaces in filmed SF. In one way, it’s an aesthetic judgement; things simply look more interesting if they’re a bit battered and work-roughened. Take a look at the Star Wars universe, where everything is pitted, dirty and worn with use. In Elysium, and its thematic twin, Pete Travis’ Dredd, that judgement is part of the narrative. Megacity One doesn’t have the organically swooping towers and bulbous arcologies of the comics. Instead, it looks like a smog-choked Chinese city, thrown up in a hurry with any materials to hand.

There’s a common complaint with both films that the future doesn’t look futuristic enough. Elysium is set in 2154. Although undated in the movie, the universe of Dredd is set around the 2130s. And yet, the population still gets around largely on familiar cars and buses, and are dressed in a way that wouldn’t, for the most part, look out of place on the streets today. The opening sequence of Dredd involves a chase scene between the Judge and a bunch of miscreants in a VW camper van. If we extrapolate the gap betweens those films and us the other way, we’d be in the 1870’s when steam was the fastest way to travel, and flight was still decades in the future. Where, then, are the wonders of the future?

The wonders of the future

The wonders of the futureWell, apart from the fact that Elysium features a giant orbital habitat, and people-traffickers with spaceflight capabilities, the backwards nature of some of the tech is kind of the point. The poor, teeming masses in Travis and Blomkamp’s purgatorial megacities have to survive with whatever they can get their hands on. If that means retro-fitting old cars to get around, then so be it. These are effectively third-world urban structures. All the wonders of the future are either up in orbit, or blown away in a nuclear wind.

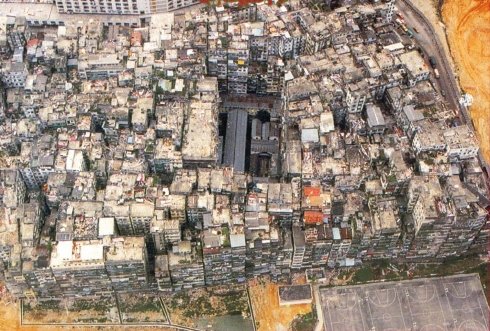

The point is that these cityscapes can’t easily be tied to one particular time. As we can’t accurately place them in the past or present, they are equally believable as a futurescape. This blurring of temporal boundaries is common in the built spaces of science fiction. Just look at Blade Runner’s retrofitted LA, with the skin of the new laid over the bones of the old, and arcologies that look as much like Aztec temples as they do science parks. Godard’s Alphaville was famously shot in contemporary Tokyo, scenery so otherworldly that it could be easily passed off to credulous 1960s audiences as another planet. Similarly, Michael Winterbottom’s Code 46 was partially shot in Dubai, a built environment that’s an alien intrusion to the sun-baked desert that it contains. I’m also reminded of structures like Kowloon Walled City, the slum/fortress in the heart of Hong Kong that, in the 60s and 70s, was the first real Dredd-style mega-block–a self-sufficient city within a city.

Using existing settings and vehicles isn’t just a matter of maximising budget. It’s shorthand, a way of showing the audience that sometimes, the future isn’t going to be as magical or overwhelming as we think. By using the slums of Mexico City and the streets of South Africa, the directors of Dredd and Elysium are keying into a deep history of corrupt governance and endemic poverty, and using t to underpin the stories they want to tell. When people look at our lives in the 21st century and ask “where’s my jetpack?” (it’s here, by the way) they aren’t seeing the whole picture. Huge chunks of the planet don’t even have decent access to clean water, let alone flying cars and robot coppers. Dredd and Elysium are using their dystopian settings to show that the future could be a lot more broken than we choose to imagine.

Nice, skim-read only until seeing E next week with LMC. Though I do agree to an extent, one shouldn’t underestimate the budgetary aspect, which is massive. South Africa is, as I’ve blogged on several times, rapidly becoming the go-to location country for this reason, as well as its freshness. You’ve also anticipated a new project of mine – More later!

Thanks, Chris. Hope you don’t think I’m treading on your toes with this one.

I was drawn towards watching Dredd again after seeing (and enjoying) Elysium, and the piece just came out of the obvious comparisons between the two. Also: fascinated by Kowloon Walled City.