Between 1844 and 2013, HMP Reading was the involuntary home for thousands of people who had caused offence to the state. From its original aim as a new model prison, with design features considered progressive for the time, the building changed, grew and mutated. Over the decades it became shabby, gradually less fit for purpose. Finally, after service as a young offenders lock-up, it was closed three years ago.

And that would have been the end for this unlovely, haunted building, if not for the fact that it is world-famous under its original name. Or rather, because of one particular inmate. Between 1895 and 1897 Prisoner C.3.3 suffered, wrote movingly of his torments, and immortalised the building whose walls enclosed him.

We know the man as Oscar Wilde, and the building as Reading Gaol.

The future of The Gaol has been under question since the last prisoner left. The historical significance of the place is beyond doubt, but the Ministry of Justice is unwilling to release it to the public, hinting darkly that it may be pressed back into use at an unspecified future point for an unspecified future purpose. However, the site-specific installation group Artangel, as part of Reading’s Year Of Culture, has pulled off something of a coup. They’ve shown just how appropriately the building can be used as an arts venue.

Meanwhile, in the chapel, readers await. On our visit, actress Maxine Peake, sombre in black, sat on a plinth designed by Jean-Michel Pancin to the same measurements as a Reading prison cell. Behind her, the original door to C.3.3 glowed in autumn sunlight. At mid-day, she began to read Wilde’s most passionate and revelatory work, De Profundis. This hundred-page letter to his lover and tormentor, Lord Arthur Douglas, is part confession, part therapy, part consideration on the nature and creation of art. The readings take an average of four hours to complete–a marathon task. This has not deterred other famous figures from taking on the challenge. Over the course of the event, actors Ralph Fiennes and Ben Whishaw, writers like Colm Tóibín and performers of the calibre of Patti Smith will read the piece just yards from the cell where it was written, on Wilde’s permitted ration of four sheets of foolscap per day.

The visit is one that puts a load on you. The sheer weight of thick stone presses in. Bars and grilles put a grid over every sight-line, chopping and splitting the light. Inside each cell, graffiti speaks of lives put on hold, the drag of days that pass like weeks, of hours that pass like days. There’s little sense here of the improving mission of Reading Gaol’s architect, George Gilbert Scott. This is a place to sit and wait. A place to survive. The sad little bits of posters left on the cell walls, stuck on with toothpaste as the prisoners were not allowed blu-tack, feel almost like a tiny portion of an inmate’s soul, left behind as tribute or payment. Punishment always has a cost.

For Wilde, the cost would prove too high. Broken by the experience and estranged from his past life, he died in 1900. But the years he spent in Reading Gaol redefined him as an artist with a profound and tragic sense of the transformative power of art. De Profundis speaks to us even now as a work of impact and import, allowing us to understand that love and forgiveness are more powerful forces for good than punishment and imprisonment. His legacy, and that of the thousands of other souls that passed through the heavy gates of Reading Gaol, should be remembered.

Inside continues at the former HMP Reading until early December. Tickets for the readings are long sold out, sadly, but don’t let that deter you from a visit to one of the country’s most unusual and affecting art happenings.

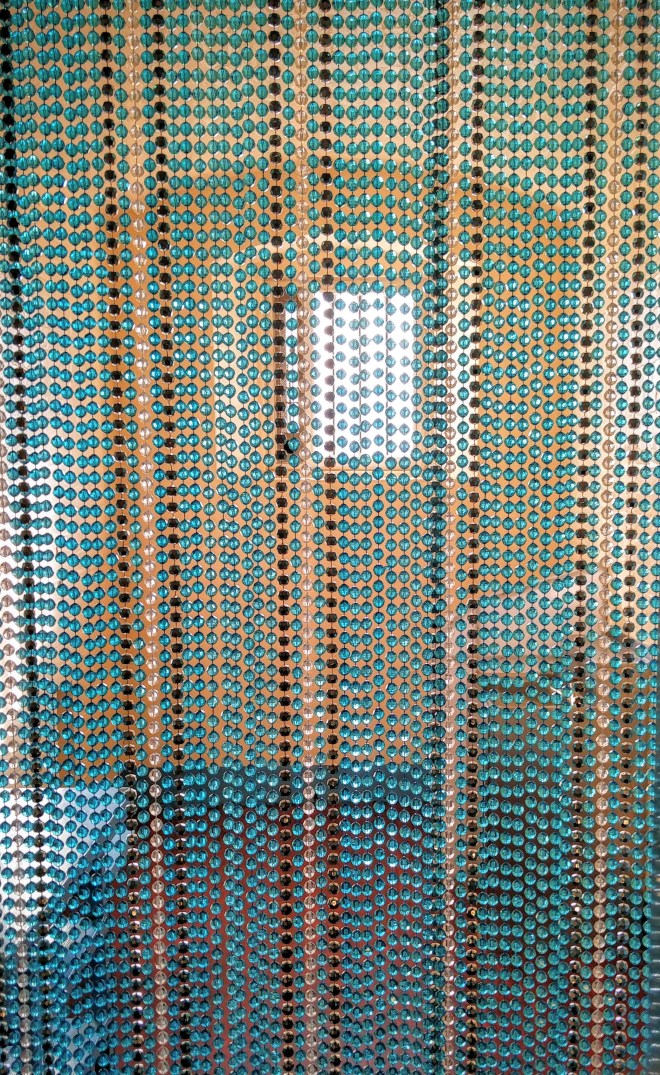

(Featured image: ‘Oscar Wilde’ by Marlene Dumas)

Small correction Rob – it’s ‘Ministry’ of Justice here, as we’re not quite that American yet!

Noted and corrected. Thanks!